Anchor snubber design is straight forward but bridle design is slightly more complex. Many folks don't realize the choice of hooks limits the options on bridle types and vice-versa. The two most common types of bridles are Y-spliced and two independent legs. Y-spliced bridles will accept most hooks but with independent leg bridles it's trickier.

Snubbers

Snubbers, at the most basic level, are a single elastic line secured to a chain rode with a hitch or knot. This design has proven effective but it has limitations and has thus evolved. Most snubbers sold on the market today are made from 3-strand nylon, have a hard eye (spliced eye with a thimble), a shackle to attach a hook, and, of course, the hook. Most have some form of anti-chafing protection. The components are sized based on the weight, length and windage of the vessel as well as the expected conditions. Snubbers have few limitations on choices of hooks but some designs are significantly stronger than others.

Basic

A simple line and a hitch for snubbing is still fairly popular, especially with old salts. Braided nylon line and recycled climbing rope are common because they are elastic and easier to tie than 3-strand. The rolling hitch, icicle hitch and the prussik knot (requires a loop of rope or sling) are common hitches and knots used for attaching the line to the chain rode. Some hitches have better holding power than others (icicle), some are more difficult to remove after being wet and loaded (rolling) and others are less impactful on rope strength (prussik). This basic snubber can be had for the cost of a length of line and the time invested in a YouTube video or Animated Knots tutorial on how to tie a hitch.

Designs with Hooks

If the thought of a hitch on a chain standing between staying set or dragging anchor on a windy night isn't your idea of security, you should consider a hook. Given the scope of the topic, we've dedicated a full page to it. Check out our snubber bridle hooks page for details. Next up, how to attach the hook to the lines.

Line Spliced or Tied Directly to Hook

There are four common methods of attaching the hook: a simple knot (bowline is common),

splicing the line directly to the hook, splicing a hard eye directly to the hook, or attaching the hook using a shackle. I'll address the latter two in the next section.

Whether you tie a knot or splice the rope directly to the hook without a thimble, the resulting rope strength will be

reduced by half. Ok, that makes sense for knots but doesn't a splice preserve much of the rope's strength? Yes, but when the line is bent 180° around the

small radius of a hook's eye (image lower right), then the rope's strength takes a ~50% hit. Sure, increasing rope size might solve the strength issue but it's less elastic for a given

length than smaller diameters and much of the snubbing benefit is lost. If you choose to splice directly to the hook, remember it's another splicing effort

and 1-2 feet of line to change the hook out. Either way, if you're going directly to the hook, check the eye carefully for burrs or rough areas that might accelerate

chafing. If it was a windy night and I was on the hook with this design, I would probably have my head sticking out the deck hatch most of the

night checking for drag.

[Image: left - hook tied with knot, right - line spliced directly to hook's eye]

Hard Eye Designs

In the author's opinion, if you're going with a snubber instead of a bridle, this is the design that provides a peace of mind when the wind kicks up.

If sized appropriately, snubbers with hard eyes and bow shackles accept most hooks and are ideal for everyday use and even a hard blow. This design

preserves more of the rope's strength than other designs. A splice typically reduces rope strength by ~10% and the bend around the thimble deducts

another 10%. That's right, 20% right off the top, but it's better than the 50% - 60% using the methods above. If the hook's eye will accept a

thimble directly, you can eliminate the shackle; however, using a shackle makes it easy to change hooks. In addition to maintaining a large radius

bend to preserve rope strength, the thimble reduces rope chafe on the eye as it lies between the rope and the hook or the shackle. Boats that are heavy

for their length and/or have a high wind profile should probably opt for heavy duty thimbles.

[Image: Common snubber design sold by manufacturers]

Bridles

There are probably dozens of variations on anchor bridles, but the two most common types are Y-spliced and two independent legs.

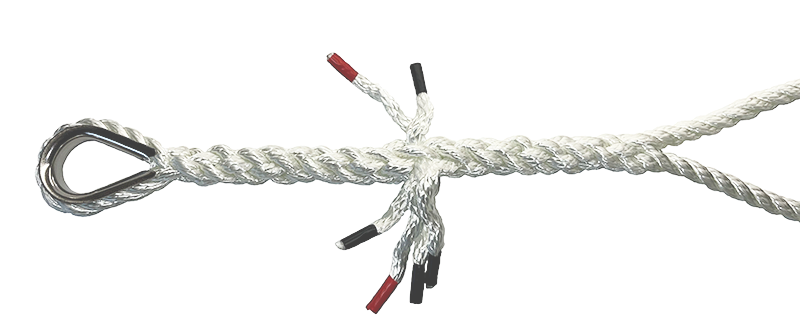

Y-Spliced

Y-spliced bridles are essentially a single line snubber with a 2nd line spliced into it. Many manufacturers use

this design since it affords the consumer a wide array of hook options

(since the bridle has a single eye like a snubber, most hooks should work). Similar to the snubber designs discussed above, consider a design

using a hard eye and shackle to attach the hook. The greatest downside to the Y-spliced bridle is it lacks two fully independent

legs; the point from the Y splice to the hard eye is essentially a single line. This design does not provide full redundancy or a significant increase

in strength similar to the independent leg bridle.

[Image: Y-spliced bridle during fabrication]

- Ideal for monohulls and boats that are not excessively heavy for their class. Vessels with significant wind profiles or that are heavy for their class should consider independent leg bridles.

- Fair-weather, weekender or other boaters unlikely to be caught in a severe storm should be fine with this bridle type.

- Full-time cruisers should opt for two independent legged bridles if possible. The range of conditions and the likelihood of getting caught in a storm are greater - having full redundancy in the lines seems like a safer bet

- Y bridles should not be used on catamarans unless the bridle has long legs and the full length of the legs is deployed in all but the lightest wind. With the wide beam on catamarans, short deployments create a wide inside angle where the 2nd leg is spliced into the primary one. Taking a cue from the lifting industry, loading a bridle with a high inside angle can cause extraordinary loads on the splice and the lines. For a detailed explanation and images see the Catamaran Anchor Bridles page

- This design should NOT be used for storm bridles

Bottom line: Y bridles are commonplace, and failures are seemingly rare on monohulls. Heck, I build and sell them at 49° North Marine, but, let's face it, they are a compromise (albeit small) due to the lack of hooks that can accommodate two independent legs.

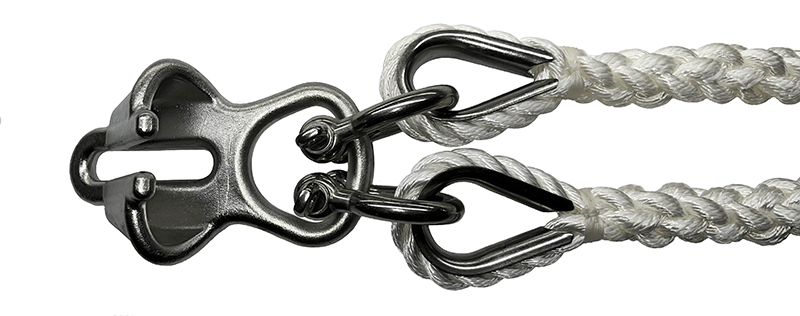

Independent Legs

Bridles made from two independent lines provide strength and redundancy where bridles fail most often: the rope. The primary issue with this bridle type is only a few hooks are designed to accommodate two independent legs. Most hooks on the market do not readily support independent legs without over-sizing the shackle.

Hooks with multiple eyes (Seadog Chain Gripper Plate) and hooks with large eyes (Victory Hook) are designed to support bridles with two independent legs. These hooks are manufactured by brand name companies and have been on the market for many years, but neither, unfortunately, are load rated. Most other hooks on the market are not well suited for independent legs and require a grossly over-sized shackle to adapt them. I use "grossly" with intent here. Simply upsizing the shackle to the first size that will accommodate two hard eyes is not viable; the thimbles will not sit correctly in the shackle. Shackles need to be upsized by 2 or 3 sizes to provide ample room for the thimbles. Example: A pair of 3/4" thimbles (or hard eyes) will fit into a 5/8" shackle but the thimbles hang from their edges. A 3/4" shackle will allow some thimbles to seat well, but a 7/8" or 1" shackle may be required for others. Assuming a 3/4" SS shackle can be used, that's 2 lbs of shackle with a cost (at the time of this writing) of $59.00 for the cast version and $146 for the forged version. A 7/8" SS shackle is 4.3 lbs, $66.00 for cast and $167.00 for forged. A 1" is 5 lbs and $96.00 for cast (I didn't want to look at the forged cost!). These are beasts; hence my choice of the adverb "grossly".

Bridles with two independent legs are probably the better choice, but considering the limited number of hooks suited for this design, or the mutant shackle requirements

to adapt incompatible hooks, it's easy to understand why y-splice bridles are popular.

[Image: Bridle w/ 2 independent legs on Victory style hook]

Brummel Splice

Brummel spliced bridles are uncommon but are sold by a couple of manufacturers. Brummel splicing requires plaited or single-braid rope and tucks the rope back through itself multiple times creating an eye. Brummel splicing on a bight in the middle of a length of rope yields two legs to form the bridle. If you're unfamiliar with this splice check it out at Brummel Eye Splice | Animated Knots. While this design can use any hook on the market, its strength is equivalent to a single line, similar to the Y Bridle above. It's solid for the weekend boater and, hey, it sure looks nice, too.

Two Snubbers in Tandem

Deploying two snubbers in tandem extends all the benefits of a bridle - superior strength and full redundancy across all components: rope, shackle and hook. This assumes the snubbers are made with hard eyes, and the rope, shackle and hook are appropriately and similarly rated. Deploy one leg as a snubber and when the wind pipes up or the motion becomes uncomfortable, add the other snubber and enjoy the benefits of a bridle. This method works well with eye-grab hooks and hitches when attached to consecutive links. Unfortunately, most other hooks would have to be spaced too far apart, rendering this method mostly ineffective.

Storm Bridles

When you consider the kinetic energy of a boat squares with an increase in boat speed of one knot, you understand the load a snubber or bridle is subjected to in a gale. While not having personally experienced winds greater than 50 knots at anchor or a bridle failure, I've heard from readers on how their bridles failed. Here are some design considerations for a storm bridle:

- Don't use a snubber - a bridle is the better option; think redundancy.

- If you are a seasonal, fair-weather, weekend sailor and planning to purchase a bridle, don't buy a storm bridle for everyday use. Right-sizing for the conditions typically experienced is the better approach or you lose the benefits a bridle provides.

- If you are a part or full-time cruiser, or someone who is likely to get caught in foul weather with some regularity (fair-weather sailor living in the higher lattitudes), consider purchasing an everyday bridle AND a storm bridle.

- Lines should be sized up in diameter and length - many cruisers state their storm bridles are 25% longer than their boats.

- Buy rope from a reputable manufacturer and check its Working Load Limit (10% - 20% of tensile strength; we use 12%). If it's made to the Cordage Institute's standards, all the better.

- Hardware should be sized up AND upgraded. Shackles should be forged and sized for the increased load

- Load rated hooks that cradle the chain link are recommended

- Heavy-duty thimbles are an imperative. Heavy-duty captive or closed thimbles are best. If an open thimble is used, seizing must be done just above the thimble's apron (e.g. near prongs at the opening of the thimble)

- Seizing should also be done on the rope splice immediately below the thimble's apron. Yes, you read that correctly, seizing the rope to the thimble directly above the thimble's apron, and again on the rope splice immediately below the apron.

- Seizing should be done with 1.5mm or larger whipping thread or sailmaker's thread (at 49°North, we use #7 sailmaker's thread) and should be tied off multiple times through the course of seizing for redundancy. Why all the extra seizing? Under extreme loads, the rope stretches and the thimble can fall out or turn in the eye causing the prongs to cut into the line.

- Size the components of the storm bridle system using the Working Load Limit for the rope, shackle and hook to meet the load of the boat. Again, building in a safety factor is important but not excessively over-sizing is important. Try plugging your boat details and anticipated conditions into our sizing calculator. and notice the difference between 1 knot (everyday, fair-weather) of boat speed at anchor vs 2+ knots (storm conditions). The results might surprise you.

Boat End

We've been writing about the chain end but what about the boat end? Some manufacturers add soft eyes while others leave the ends untreated. Bridles for catamarans frequently have hard eyes spliced into them for shackling to bow eyes. Sailors are never short on opinions but I haven't heard an argument strong enough to sway me out of the "it's purely personal preference" camp. Interjections:

- Soft eyes can be convenient and encourage a full deployment, but I rarely deploy all 50' of our bridle. For me, the soft eyes might be used half-a-dozen times in the 50 - 75 nights we're out each year. Further, what happens when you're head-to-wind and you're broached by swell or current? You venture out in your PJ's, pull in one bridle leg until the motion improves, cleat hitch it, take a gander at the stars and go back to bed. For others, perhaps they have a Samson post, or use a shorter bridle that is always fully deployed and have the ability to stow the bridle on deck; soft eyes would be ideal. If you request soft eyes, you should consider having anti-chafe spliced into them. Finally, if you like the inexpensive tubular anti-chafe, you can't replace it without unsplicing the eye - you have to upgrade to the fancy velcro stuff or re-splice the end.

- A naked bitter end is my personal favorite - melt, treat and whip the end - life is good. Inexpensive tubular anti-chafe is easily added or replaced, and can be adjusted to wrap the cleat hitch, the lines as the pass through chocks or hawses, or to cover the bow roller for snubbers. Naked ends are less expensive all the way around.

- Hard eyes are commonly used with catamarans and smaller monohulls where they attach directly to bow eyes with shackles. This configuration encourages full deployments (important on catamarans; see our Catamaran Bridle page for details), eliminates chafing and makes deployment easy. It also allows adjustments for motion by retrieving line on one side and cleating it. Whether or not anti-chafe should be added to the line probably depends on how frequently you make motion adjustments.

Regarding soft eyes and untreated ends, there's no wrong decision. If, in the end, you feel like you've made the wrong decision, it's easily remedied with a YouTube video and a fid.